Cooperation Cube

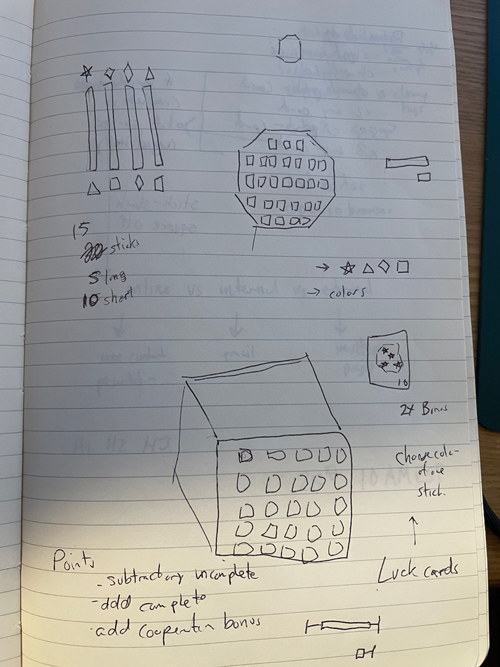

It was somewhere over the Pacific, maybe six hours into the thirteen-hour flight from Narita to Dulles when I started sketching out an idea in my notebook.

The cabin was dark. Most passengers were asleep, window shades pulled down against the artificial night. I had my light on, a half-drunk ginger ale sweating onto the tray table, and the mechanical pencil I always keep in my carry-on.

The notebook was already covered in scratches. A cube. A few holes. Lines connecting them.

I didn't know it yet, but I was designing something that would take a couple of years to become a finished physical object, and would teach me more about the gap between creation and distribution than any software project ever had.

The idea didn't come from frustration. It wasn't about solving a problem.

I just wanted to invent something.

There's a particular itch that comes from building software all day. Everything you create exists only as abstractions, logic gates and database rows you can't touch. Sometimes you need to make something you can hold.

Years earlier, I had scratched that itch, at least a little, with Putter King. Part of it was software: a mini golf game I designed in Google SketchUp. I drew the holes on my laptop, curves and ramps and obstacles, gave them to the actual game developers, and then watched in disbelief as they actually worked. Players found them fun. The difficulty progression felt natural. The physics behaved the way I'd imagined.

But I also built something real for a marketing event. A physical mini golf hole, assembled in the parking lot of a Japanese home improvement store, because my apartment could barely fit a futon, let alone a mini golf hole.

That experience left a residue. The memory that sometimes, if you're lucky, the thing in your head translates cleanly into the thing in the world. That creation can feel less like struggle and more like discovery, like the idea was already there, waiting to be found.

I wanted that feeling again.

The influences were simple enough.

I kept thinking about Hearts. Specifically, about shooting the moon.

If you've never played, here's the setup: in Hearts, you're trying to avoid collecting hearts and the queen of spades. Every heart is one point, the queen is thirteen, and at the end of each hand, whoever has the most points is losing. Simple enough.

Except there's a twist. If you collect all the hearts and the queen, every single penalty card, you don't get 26 points. Instead, everyone else gets 26 points, and you get zero.

It's called shooting the moon, and it's beautiful.

You can be sitting there, collecting hearts, while everyone at the table thinks you're an idiot. "Poor Kevin," they're thinking. "He's going to lose." Then the final card drops, and suddenly you've won, not despite collecting all the pain, but because of it.

That mechanic stayed with me. The idea that apparent weakness could be hidden strength. That the obvious interpretation might be wrong.

The other influence came from social deduction games like Mafia and Werewolf, that whole genre where hidden roles create hidden agendas. I loved the core tension: cooperation that's contingent, alliances that might be real or might be theater.

What if you needed your opponents to succeed—but not too much?

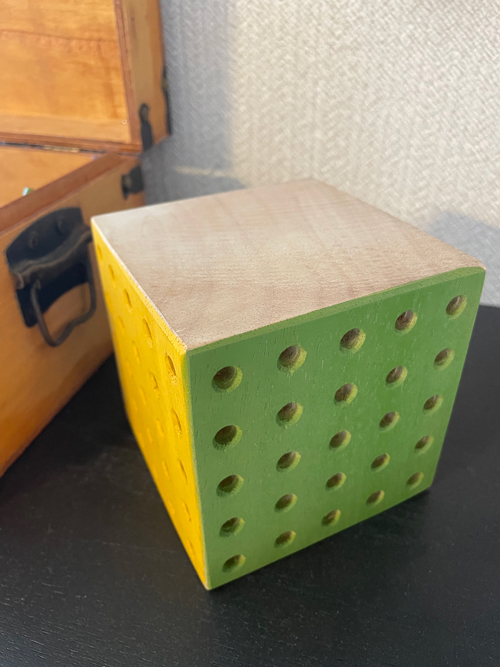

Somewhere over Alaska, one notebook page became three. The cube emerged first. Four players. Four sides. Each player can only see, and only play on, the face in front of them. The cube rotates after every four moves, so the board you're building on keeps changing. Your perfect setup becomes someone else's puzzle.

Then the sticks. Short ones that stay on a single face. Long ones that pierce the entire cube, creating connections and constraints that affect multiple players at once.

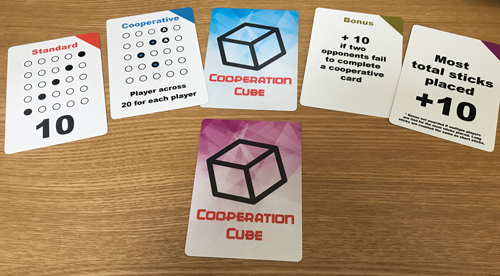

Then the cards. Patterns to complete. Some you do alone. Some require cooperation: your piece here, an opponent's piece there. You both score if it works. But you can't show them your card. You can only describe what you need and hope they believe you.

And this is where Hearts came back. The switch-seats bonus card. You play it after everyone has spent the game cooperating with teammates, just in time to roll a grenade across the table.

You can't win alone. But you can't trust everyone either.

By the time the plane touched down, I had the whole thing sketched out. Rules, scoring, card types, the rotation mechanic. All of it.

The flight landed. Then I did something unusual. I actually built it.

That's where most ideas die, not from rejection, but from neglect. The initial spark fades, life gets busy, and the notebook page becomes a relic of enthusiasm you no longer feel.

But something about this one felt different. Maybe it was the physical nature of it. Software is abstract. You can't hold a well-designed database schema. But a wooden cube with holes drilled through it? That was tangible.

I wanted to hold it in my hands.

The first prototype was humbling.

I cut a solid wooden block from scrap wood my dad had in the basement and marked a 5×5 grid on each face. Twenty-five holes per side, each one needing to align precisely with its opposite so a long stick could pass through cleanly.

I drilled the first hole and immediately understood the problem.

The bit wandered. Not much, maybe two millimeters by the time it exited the other side, but enough that the long sticks wouldn't fit. They'd bind halfway through, come out at an angle, or require so much force that the wood started to split.

I tried drilling from both sides, meeting in the middle. The holes didn't line up. I tried using a drill press for better control. The bed wasn't deep enough for a six-inch cube. I tried longer drill bits. They flexed and drifted even worse.

The first cube went into the scrap pile. Then the second. Then the third.

We built guides. Jigs to hold the cube in alignment. Each improvement helped. None of them solved the problem completely.

The truth is, we never got a perfect setup. Even with the guides and the jigs, each hole still required patience and precise execution. One moment of inattention, a slight wobble, a push at the wrong angle, and the bit would drift. Once one hole was off, the whole cube was ruined.

For every successful cube, five or six blocks went into the scrap pile.

I still have some of those failures stacked in a corner of the workshop. Twenty-four holes drilled perfectly, and then the twenty-fifth wandering just enough to bind the stick. Hours of work, discarded because of a millimeter.

The sticks were their own journey.

Dowels. Cut to length. Ends sanded smooth. Painted in four colors, red, yellow, green, and blue, one set per player. Fifteen short sticks and five long ones each.

I built a simple cutting jig, a piece of wood with a stop block so every cut would be identical. Then came the repetition. Cut and sand. Cut and sand.

And then something remarkable happened.

We played it. And it worked.

Not "worked after extensive playtesting and iteration." Not "worked once we fixed the broken mechanics." It just worked. The rules made sense. The strategy had depth. The cooperation cards created exactly the tension I'd imagined, that delicate balance between needing your opponents and not trusting them.

It was balanced. It was fun. The game I'd sketched on a notebook over the Pacific translated almost perfectly into the game on our living room table.

Like Putter King all over again. That strange magic when the thing in your head matches the thing in the world.

The only real change came from my brother-in-law, during an early session. He kept losing track of which face he'd been working on when the cube rotated.

"What if each side was a different color?" he asked. "Just to help you remember?"

It was obvious the moment he said it. I painted four faces to match the player colors, red, yellow, green, and blue, and left the top and bottom as natural wood. Suddenly the memory problem disappeared. You could glance at the cube and instantly recall, "I was on the green side. That diagonal I started is still there."

That was it. One suggestion. The rest of the design held.

The painted cube sits in a wooden chest now, the kind you might find in an antique shop, with brass hinges and a latch that clicks when you close it. Inside are the cube itself, four faces painted to match the player colors and two left as natural wood. A deck of cards in a white box. Four velvet bags, each holding one player's sticks.

It looks like a real game. A thing that could exist on a shelf next to Ticket to Ride and Catan.

There's just one problem.

Fewer than five of these cubes exist in the world. Each one represents a small graveyard of failed attempts, the blocks that didn't make it, the holes that drifted, the hours that ended in sawdust and frustration.

The game worked. The manufacturing never did.

Every cube requires patience and perfect execution across every single hole. One mistake on hole forty-seven and you start over. There's no recovery. No fixing it. Just another block for the scrap pile.

So Cooperation Cube remains what it is: a handmade curiosity.

The obvious solution is digital.

Build it as an app. Render the cube in 3D. Let people play online, across distances. Suddenly the manufacturing problem disappears. Suddenly distribution is trivial.

I've started this project three times. Each time, I get a few evenings in, wireframes sketched, basic cube rotation working, and then I stall.

Part of it is energy. After eight-plus hours of programming for my day job, the last thing I want to do is program for my side project.

But there's something else. Something I don't fully understand but feel in my gut.

The game is meant to be played at a table.

Not because the mechanics require it. They would translate fine to a screen. But something essential would be lost. The weight of the wooden cube. The satisfying click of a stick sliding into a hole. The way you can watch an opponent's face when they realize they've been bluffed.

I worry that a digital version would be technically correct but spiritually empty. That it would capture the rules but lose the game.

Maybe that's an excuse. Maybe I'm just tired. Maybe I'm protecting something that doesn't need protection.

But the app remains unfinished. And the cubes remain rare.

Cooperation Cube stays in its wooden chest, waiting for the next time I can gather four people around a table.

My son asked me once why I spent so much time on a game we'd only played a dozen times.

"Wouldn't it have been easier to just buy one?"

I thought about it for a moment. He wasn't wrong. The hours I spent cutting sticks, drilling holes, and painting faces could have bought fifty games.

"Probably," I said. "But then it wouldn't be this game."

He looked at me blankly. He's eight. The distinction didn't land.

But someday it might. Someday he'll make something himself, not because it's efficient, but because the making is the point. Because he wants to see if the thing in his head can become a thing in the world.

And when that happens, maybe we'll sit down with the cube and I'll tell him the story. The flight. The notebook. The failed prototypes. The scrap pile that grew faster than the finished products. The game that worked on the first try and still couldn't find its way into the world.

Then we'll play. At a table. The way it's meant to be.

And maybe that's enough.