Problem before plan

It was the week after Thanksgiving, and I did something that felt a little unconventional.

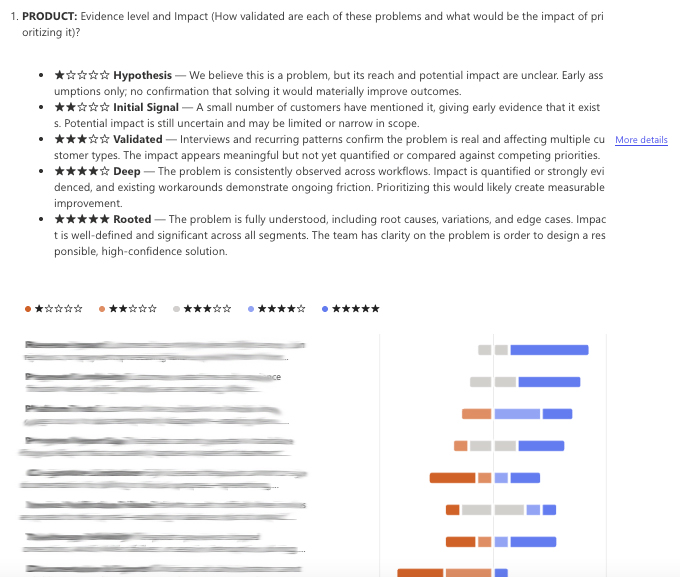

Instead of sending my team a Q1 2026 roadmap, I sent them a survey. Two, actually.

The first asked everyone to list the top three problems they thought we should solve in Q1. No features. No solutions. Just problems.

The second asked them to rank their teammates' submissions based on evidence level and potential impact.

Here's what usually happens at the end of a quarter: Investors want to see a plan. Sales has a list of deal blockers. Support has a backlog of complaints. And someone, usually me, scrambles to turn all of that into a tidy roadmap with dates, features, and confident checkboxes.

It feels productive. It looks like leadership.

But I've been doing this long enough to know the trap.

Ten years ago, customers came to us with pain.

"Our therapists are drowning in paperwork,"

"We're losing track of who owes what,"

Vague complaints about "the way things are."

That's no longer the world we live in.

Today's customers are power users. They use dozens of apps every day. They've experienced brilliant UX and terrible UX. So instead of describing their problem, they describe the feature they think will solve it.

"Do you have autopay?"

"Can we export this to Excel?"

"When is SMS coming?"

It sounds like clarity. It's actually a trap.

Once a customer hands you a feature, saying no gets harder. Interviewing them gets trickier. And look, they might be right (and often are). You might end up building exactly what they describe.

But there's risk in taking the request at face value.

You can miss an entirely different solution, one that doesn't just satisfy the immediate ask but removes a whole class of problems you'd never connected in the first place. And you risk turning your product into a pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey board of features: each one reasonable on its own, together adding up to something with no clear vision.

None of this is new. "Start with the problem" isn't some breakthrough insight. It's Product 101.

The hard part isn't knowing that you should start there. It's noticing when you haven't.

In today's world of tight deadlines, investor pressure, and support tickets that read like feature specs, it's easier than ever to skip the problem step without even realizing you've done it. A request shows up fully formed. It feels concrete. Actionable. Irresponsible to ignore.

And just like that, you're building again.

This year, we tried something different.

We called it the Problem Atlas.

It shows the topography: the peaks and valleys of what's broken, who feels it, and how much it matters. But it isn't a roadmap. It doesn't draw the route. It doesn't prescribe solutions.

What surfaced wasn't surprising. Billing consistency. Post-release stability. Onboarding friction. Demo capacity bottlenecks.

But the conversation felt different. Instead of "we need feature X," we asked, "What would tell us this problem is gone?"

I won't pretend we've figured it all out. This quarter, we're experimenting with organizing people around problems instead of org charts.

But I can tell you this: those meetings felt different. Lighter. More engaged. More honest.

The hardest part of building products isn't knowing how to build things.

It's resisting the urge to build before you understand what's worth building.

That's the discipline we're practicing heading into 2026. Not a roadmap. An atlas.